Privacy Policy Analysis

We studied the deployment of computer-readable privacy policies encoded using the standard W3C Platform for Privacy Preferences (P3P) format to inform questions about P3P's usefulness to end users and researchers. We found that P3P adoption is increasing overall and that P3P adoption rates greatly vary across industries. We found that P3P had been deployed on 10% of the sites returned in the top-20 results of typical searches, and on 21% of the sites returned in the top-20 results of e-commerce searches. We examined a set of over 5,000 web sites in both 2003 and 2006 and found that P3P deployment among these sites increased over that time period, although we observed decreases in some sectors.

In the Fall of 2007 we observed 470 new P3P policies created over a two month period. We found high rates of syntax errors among P3P policies, but much lower rates of critical errors that prevent a P3P user agent from interpreting them. We also found that most P3P policies have discrepancies with their natural language counterparts. Some of these discrepancies can be attributed to ambiguities, while others cause the two policies to have completely different meanings. Finally, we show that the privacy policies of P3P-enabled popular websites are similar to the privacy policies of popular websites that do not use P3P.

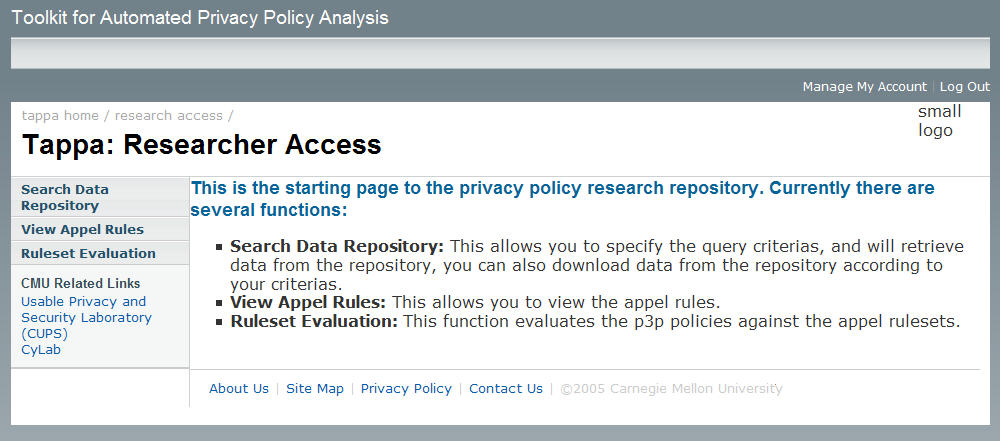

TAPPA

TAPPA (Toolkit for Automatic Privacy Policy Analysis) is a toolkit that aims to provide decision makers and policy analysts a quick snapshot of the state of privacy policies. It consists of both machine readable policies (P3P) and natural language policies. For a given policy, metadata are collected on these policies (such as top level domain, country of registration, website keywords, website traffic rank). Traditionally privacy policy analysis is a time consuming task (FTC 1998, FTC 2000). This toolkit aims to alleviate some of these burdens into automatic processing.

Figure 1 TAPPA Research Menu Screenshot

CPIG Study

In an attempt to bring privacy information to users earlier in their interaction with websites, AT&T Labs researchers developed a prototype "privacy-enhanced search engine" that annotates search results with P3P information. We extended this work to develop a more robust P3P search service called Privacy Finder. Privacy Finder employs a large policy cache so that users do not have to wait for P3P policies to be retrieved. We used this cache to study privacy policies.

While roughly ten percent of all sites studied have deployed P3P, more than twice as many e-commerce sites have deployed P3P. In addition, P3P deployment rates are highest among the most popular websites and those most frequently returned in search results. We have also shown that P3P adoption is increasing, although at a slow pace in most sectors. However, deployment of P3P by even a few additional very popular sites could substantially increase the frequency with which P3P-enabled hits are returned in search results.

Beyond examining P3P deployment rates, we have also examined privacy policy trends. We analyzed the content of P3P privacy policies from a variety of industries and found that privacy practices vary significantly across different types of websites. P3P facilitates the collection of data on a much larger number of privacy policies than would be otherwise feasible.

Finally, we explored the differences and similarities in privacy policies between sites that choose to post P3P policies and those that do not. We used TAPPA to code P3P policies for sites that did not provide them. Among the most popular websites, there is little difference between the privacy practices of sites with P3P policies and sites without P3P policies. We found some significant differences when we examined random sites; however, the large numbers of ambiguities in the natural language privacy policies that we coded limit our ability to draw conclusions from this analysis.

Error Study

We checked P3P policies for syntactic errors and examined their accuracy. We found large numbers of syntactic errors as well as numerous discrepancies between P3P policies and their natural language counterparts. Most of the syntactic errors were not critical to policy evaluation, and many of the discrepancies did not impact Privacy Finder’s evaluation of a policy. However, these errors do raise concerns about the reliability of both P3P policies and natural language privacy policies and highlight the need for better tools for authoring and managing both natural language and computer-readable privacy policies.